25 Nov The Sagrada Familia: A Personal Response

I’ve been encouraged to share my personal response to Antoni Gaudi’s Expiatory Temple of the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, and I gladly do so. However, in responding in a personal way I have fond hopes that this will not be an entirely self-indulgent exercise.

Hope One is that how this structure speaks to me relates in an authentic way to what Gaudi is trying convey; and Hope Two is that reflection on his undertaking has a special resonance and meaning in this setting, here at the Oratory.

And this for two reasons. In his latter years Gaudi observed a rigorously ascetic discipline, rising early going to morning Mass, spending time in meditation at the Temple itself, before commencing his work. In the afternoon each weekday, he would make his way to the Oratory of St Philip Neri for prayer, confession and spiritual direction with Fr Louis Maria de Vilis.

The voiceover of a recent documentary by José Falcón Rodgrigo has Gaudi recount the following:

We agreed that my main defect was my bad temper, which I fought against but never managed to master, especially whenever any ignorant or presumptuous person tried to argue with me about architecture.

One afternoon in 1902 I received the following surprise: my friend the modernist painter Joan Llimona had used my likeness to represent St Philip Neri in two large paintings in the presbytery, teaching Christian doctrine to the people, especially to the children and the miracle of his raising up Christ present in the Eucharist. This indeed was my aim in raising up the temple of the Sagrada Familia to which I was devoting my life, intelligence and artistic abilities to display all of Christianity and to praise Jesus God and man in the miracle of the Eucharist.”

|

| [Fig. 1 – Joan Llimona, Gaudi as St Philip Neri] |

It was while on his customary walk to the Oratory that Gaudi was struck by a tram which led to his death three days later on June 10, 1926, age 73.

The second resonance comes from the Temple’s title of dedication: which it shares with this parish. This is the point at which, for me, Gaudi and the Sagrada fuse with the concerns and insights found in the French theological poet Charles Peguy born in 1873 and who died in 1914. The Expiatory Temple of the Holy Family, to use its full title, was the result of a private initiative of a Spiritual Association devoted to Saint Joseph. Amongst many things, this renewed focus on the biblical family of Nazareth sought to recover the centrality of secular life for Christianity, that is, life in the world, daily life, the life we deign to call ‘ordinary’. This was intended as a corrective to a clericalized monopoly over the holy.

I believe Gaudi, like Peguy, sensed that the Faith was exposed as never before to tremendous modern forces requiring an heroic innocence, an heroic sanctity to be lived out precisely in their midst. This situation of extreme exposure meant that each Christian, in Peguy’s phrase, lived on the front lines, under pressure, in a situation which presented this summons. Rather than conforming to or condemning the modern world, instead to embody and live the Faith in this abyss of incredulity, and in so doing, in Peguy’s words, erect a splendid monument to the presence of God, thereby acquiring a new, singular beauty in his eyes.

For me the Sagrada Familia is just such a monument, a truly creative Christian overcoming of a fight or flight reactionary relation to the contemporary. Its exaltation of the Holy Family is very antithesis of a triumphalist collaborationist bourgeois Christianity. For the focus falls on the hidden life, the interior castle of the home and the spirit, the little way of Saint Therese. In Peguy’s view it is the father of a family in the modern world who is the one most exposed, and in the greatest peril. And so Joseph is fittingly the model of heroic fidelity.

Peguy reminds us that ‘Jesus chose to live within family life, that he really effectively and historically did live this life for the first thirty years of his existence, the only years which count as a model, as a matter for imitation; the most engaged life in the world, not a life under the Rule, nor a regular life, but life in the world.’ The other three years of his public ministry, Peguy goes on to say, are another matter. Yet their fructifying source lay in the hidden years that prepared for them.

I guess it goes without saying that all Christians worth their salt are Christocentric in a very basic way. But still there are those whose spiritual attrait is towards the Father or the Spirit, or whose Marian devotion is uppermost. What I see in the Sagrada Familia, is a recentering of the entire devotional and dogmatic edifice upon the person and proclamation of Christ. Something similarly at work in the poetic theo-dramas of Peguy, and in the lifework of Von Bathazar.

Granted, looking at the unfinished structure as it stands, this recentering is not immediately apparent. In fact the reverse seems to be the case. Looking at the Incarnation portal of the Temple,

|

| [Fig. 2] |

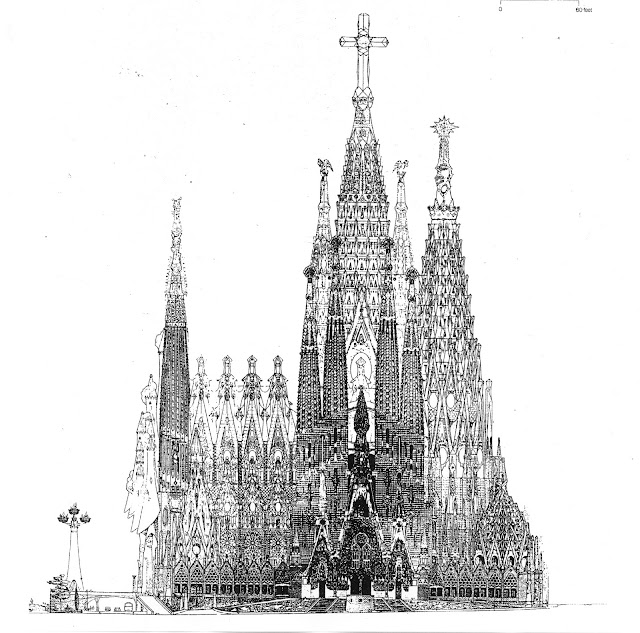

Christ is surrounded, almost submerged in creation and the human family. However, once one looks at the overall plan, its Christocentrism becomes the outstanding controlling feature of the whole Temple.

|

| [Fig. 3] |

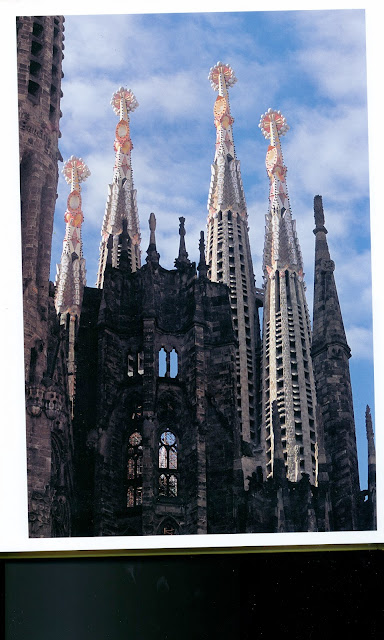

Viewed from the outside the iconography reads vertically, from the portals, through the towers upwards to the Cross atop the central spire, which Gaudi planned to be illuminated and in turn illuminate the city by means of searchlights in the surrounding towers.

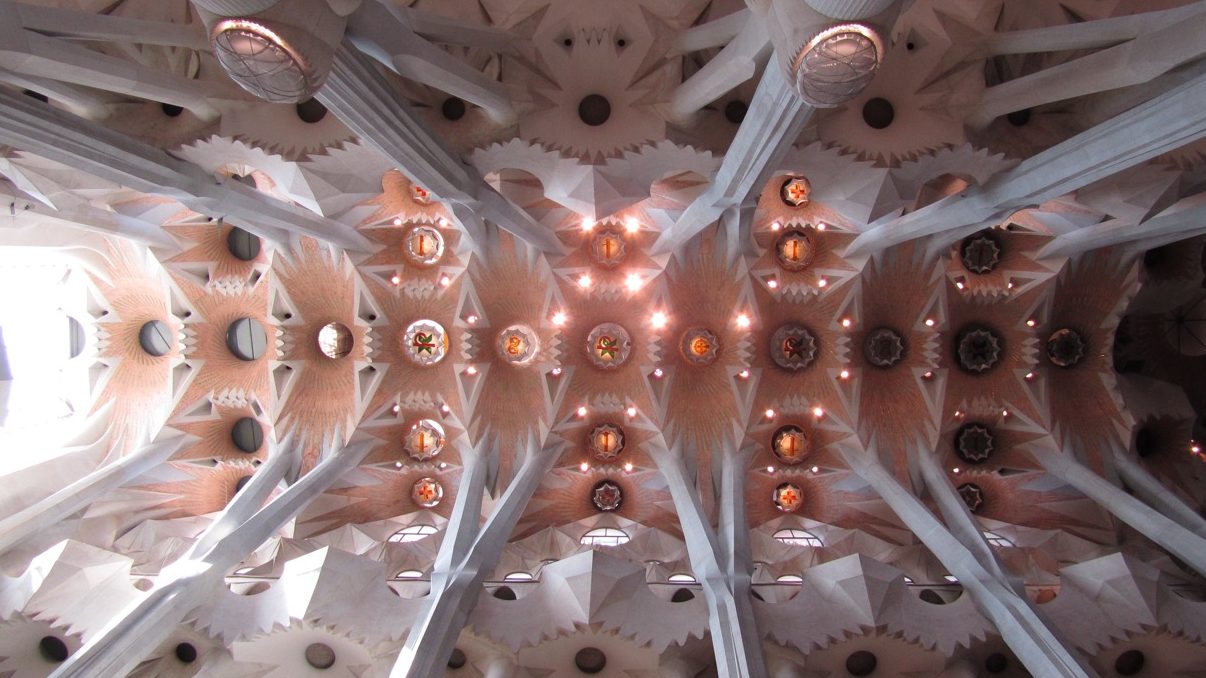

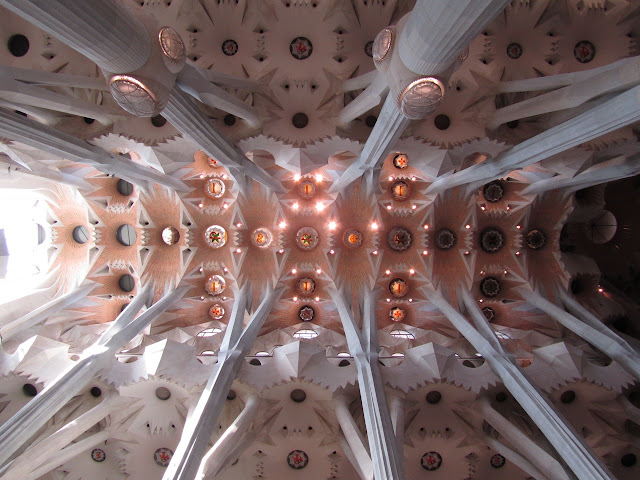

Viewed from within, for all its tremendous neck-craning height, the movement is one of descent, with light flowing down from above flooding the interior.

|

| [Fig. 4.1] |

The lines of the arboreal columns align precisely with the loads and forces generated by the tower.

|

| [Fig. 4.2] |

Instead of having to counteract and disperse these descending forces by means of exterior flying buttresses, as with the medieval cathedrals, Gaudi evolved a way of containing and harmonizing their power within the interior itself, transmitting them without a break through the columns down to the floor of the nave.

So the fundamental atmosphere of the interior is Marian: openness to God, simplicity and receptivity. Interiorly the decoration is subdued; everything centers upon the celebration of the Holy Mysteries. At the same time the Sagrada engages in proclamation to the world outside through the exuberant and elaborate iconography of its exterior.

So it is an expository Temple as much as it is an Expiatory Temple. I feel it was this impetus to proclamation that led Gaudi to profoundly modify the original neo-Gothic plan already under construction when he took over as architect in 1882. I believe the towers – and there are to be 18 in all!! – are the true key to the whole. They are witnesses and proclaimers: 4 Gospel towers and 12 Apostolic towers, grouped concentrically around Christ, with the tower of Mary crowned by a star in their midst. And these towers are alive; the Evangelical and Apostolic message continues to speak through them.

|

| [Fig. 6] |

The famous, and oft reproduced finials in which the towers culminate fuse together staff, ring, mitre and crozier – emblems of Bishops, the successors of the Apostles.

The towers are literally tongued, intended to house tubular bells Gaudi specially designed to be played from a keyboard. And the louvers, spiraling up the towers, release sound outwards and downwards, and are themselves tuned to voice the wind blowing through them. Their outline is parabolic, tracing an arc mirrored in the façades nestled within them at their foundation.

The scriptural text these towers embody for me is the following from Romans 10:14-18.

But how are they to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him? And how are they to proclaim him unless they are sent? As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who Bring good news!’ But not all have obeyed the good news; for Isaiah says, ‘Lord, who has believed our message?’ So faith comes from what is heard, and what is heard comes through the word of Christ. But I ask, have they not heard? Indeed they have; for ‘Their voice has gone out to all the earth, and their words to the ends of the world.’

The towers are Gaudi’s response to the Apostle’s question.

I’d like to touch on another aspect of the title of dedication. The Sagrada Familia was not simply to be a church, or a basilica, it was conceived as an Expiatory Temple. And this I think has served to make the entire project a flash point, a source of scandal, a stumbling block standing in the way of entering into its secret. The term expiation conjures up the image of a gloomy, ferocious, guilt obsessed Catholicism that has haunted many, James Joyce, to name just one. It is this chimaera which led to the anti-clerical riots of 1909 in Barcelona itself, and the total destruction of Gaudi’s plans and models for the Sagrada Familia in 1936 in the Spanish Civil War.

What then are we to make then of its witness to expiation? Not to mention Gaudi’s intention that the modern Temple of the Sagrada stand at the heart of civic life as the Classic Temple of the Acropolis did in ancient Athens? Well, if the Sagrada Familia’s title means nothing more than dedication to what are known as ‘family values’, then it can fairly be seen as nothing more than a reactionary in your face fortress; a Catalan equivalent of an Oral Roberts University campus for the morally upright.

But the Sagrada is anything but gloomy and ferocious. Extreme? Yes! Huge? Yes! Upon completion, it will be the largest and tallest church in Europe. But domineering? Not really. That’s because it expresses the dynamic of divine love. Peguy places these words on God’s lips: “all the prostrations in the world are not worth the beautiful upright attitude of a free person as he kneels. All the submission, all the dejection in the world are not equal in value to the soaring up point, the beautiful straight soaring up of one single invocation from a love that is free.”

The Expiatory Temple of the Holy Family is this upsurge of love set free. The perfect lover so far from domineering becomes dependent on the free response of the beloved. Expiation in the New Testament is precisely this great reversal. As Pope Emeritus Benedict writes: In the Gospel, “it is not man who goes to God with his compensatory gift, but God who comes to man, in order to give to him. This is truly something new, something unheard of, the starting point of Christian existence and the center of the new testament theology of the Cross.”

As a Torontonian living through the great condo-driven building boom, one thing that appeals to me about the Sagrada is that it is always festooned with construction cranes. It’s actually a work in progress.

|

| [Fig. 7] |

This comes as a welcome change from the endless preservation projects whose hoardings and scaffolds obscure the other architectural marvels of Europe.

To tell the truth, my immediate enthusiasm for the Sagrada Familia was fuelled by my ‘ABG’ prejudice. ‘ABG’ standing for “Anything But Gothic’. To be fair to authentic Gothic, this animus was directed against Toronto-turn-of-the-last-century knock-off Gothic.

Now at first sight the Sagrada seemed to me to pass this ‘ABG’ test with flying colours. But Gaudi, to my surprise, undermined this very prejudice. The use of computer-assisted modeling has yielded new insights into his intentions. These 3-D aeronautical design programmes have allowed the current architects to peer inside the fragments of Gaudi’s models, the only items that survived as an authoritative guide to his overall vision. Disclosed within these organic forms was Gaudi’s unique modulated geometry.

The leader in this technology, Mark Burry, has this to say: “while Gaudi appears to be de rationalizing the orthodox Gothic through the introduction of plasticity in the elements, he has invented a constructional rhetoric through the use of ruled surface geometry going far beyond revivalism or questions of style.” So now not only do I look at natural forms and, thanks to Gaudi, perceive their inner geometry, I now look at Gothic with a new appreciation for its still to be realized possibilities.

Since its inception, Sagrada has been continuously at risk of being turned into a mummified cultural artifact by the high priestly caste of curators and architectural historians. Eminent scholars like Nickolaus Pevsner along with intellectuals and the artistic Catalonian avant guard have demanded that construction stop, and Gaudi’s original facades and towers left as picturesque ruins, a monument to his unrealizable vision. Others have called for the project to be handed over to a contemporary architect to truly bring the structure into the now – perhaps the along the lines of Daniel Libeskind’s intentionally incongruous makeover of the ROM.

And yet the building continues, in fact at an ever-increasing tempo, and this despite the absence of any definitive final plan by Gaudi himself! Two factors are contributing to this momentum. At long last, thanks to the millions of tourists who visit the site annually, there is now adequate funding. The other is the use of Computer Assisted Drawing, (CAD) championed by New Zealander Mary Burry, who arrived in the ‘70s as a backpacking architecture student and who has stayed ever since. This use of computers, together with reinforced concrete to complete the structure, has caused some to question the authenticity of the finished structure.

So what, if anything, prevents the whole site from being nothing more than an ecclesiastical Disneyland? What keeps it from becoming an artificial homage to an idiosyncratic architect who founded no school, belonging to a past with no future?

I think the answer depends where you look and how. Etsuro Sotoo, one of the sculptors who has taken up the task of completing the decoration of the facades, says if we look at Gaudi alone it is impossible to discover what do now. In order to share his vision, we need instead to look where Gaudi looked, to the source of his inspiration. Then it becomes clear that for all his originality, Gaudi is deeply traditional. He received and made his own what had been handed on.

As Gaudi said, the true meaning of originality is to return to the origins, to the sources, and ultimately, to the Auctor, God the originator, God the creator. So Gaudi belongs to the 20th ressourcement theological revolution, that is, revolution understood in Peguy’s phrase as a return to a more perfect tradition.

Steadily rising, surrounded by a secular sea of rejection and misapprehension, (against the protests of the architects, Barcelona recently authorized a high speed train tunnel under the front portal) Gaudi’s Expiatory Temple of the Sagrada Familia stands as, he believed it would, not as the last exhausted gasp of an expiring Christendom, but as the first of the cathedrals of a new age of faith.

by Jonathan Eayrs, Photos courtesy of Cheryl Palmer