05 Mar Reflections on Divine Likeness

In today’s Gospel our Lord expounds a pattern of conduct which goes beyond what anyone would call reasonable:

…I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also; and if anyone would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well; and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. Give to him who begs from you, and do not refuse him who would borrow from you.

Here there seems to be no distinction between injuries or demands that are imposed justly and those that are not. Our Lord is not merely telling us that we must accept injuries that we deserve or demands upon us that are legitimate. Accepting affliction or obligation, even when they are justified, is hard enough; but clearly He means much more than this.

He means – which is already sufficiently disconcerting – that unjustified afflictions or demands must not be resisted but acceded to. But He also means that we should do more than this, not merely acceding to injustice but, from within ourselves, going beyond it: not just the right cheek, but the left as well; not just our coat but also our cloak. The left cheek, the cloak, might have been spared; but instead we must surrender them. An affliction or a demand which is already unreasonable is to be met not only without resistance, by offering as much as is asked, but with a generosity by which even the initial injustice is exceeded, in being doubled. And the injustice, being doubled, finds itself doubly transcended, its standard now subjected to an intensified irrelevance. And such intensification is without limit. We must always offer more – as much as everything we have.

Is this moral? If morality aims to strike a balance between legitimate self-interest and the legitimate interests of others, then it is surely clear that our Lord is not here offering a moral teaching. Moral teaching in this sense would begin from a perceived tension between self and other, and would then proceed to show how to manage that tension in such a way that everyone’s reasonable interests are preserved. In today’s Gospel we are faced with something very different from a moral teaching in anything like this sense.

What is it, then, that faces us? The tension between self and other has indeed disappeared, but not because of a system balancing different interests according to what is reasonable. Instead there is something much more radical: the self and its interests seem to be cancelled altogether. At least it seems as if the self is no longer a protagonist in the drama along with others, that it has ceased to be a centre of entitlement from which demands can be made and limits can be set. Instead it stands before the other ready to be entirely dispossessed: the self becoming self-less.

But why? What could possibly justify such an extraordinary demand, so different from the moral requirements we are used to grappling with? There are various ways in which we might try to make the whole thing less extraordinary, more familiar and therefore more manageable. We might wonder whether perhaps, after all, it is merely another and more subtle form of self-interest that is being offered us. Perhaps we are being drawn into a deal, a quid pro quo: if we sacrifice self-interest now, in this life, then later on, in Heaven, we will get everything back, even more than we sacrificed, and self-interest, according to an exquisite deferral, will at last be consummated, enriched beyond anything we can now imagine.

Attractive as this may in some ways sound, it isn’t the explanation our Lord gives in today’s Gospel. Instead He tells us that

[you], therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

According to this teaching we do not give now so that later on we may receive; we give in order to become perfect. And what is perfection? Its most profound meaning is that we become sons of our Father in Heaven. In other words, we become like God. In becoming perfect we come to share in the Divine life in Which everything originates, by Which everything is sustained, in Which all that is true and good and beautiful is everlastingly found. And that, one might say, is its own reward.

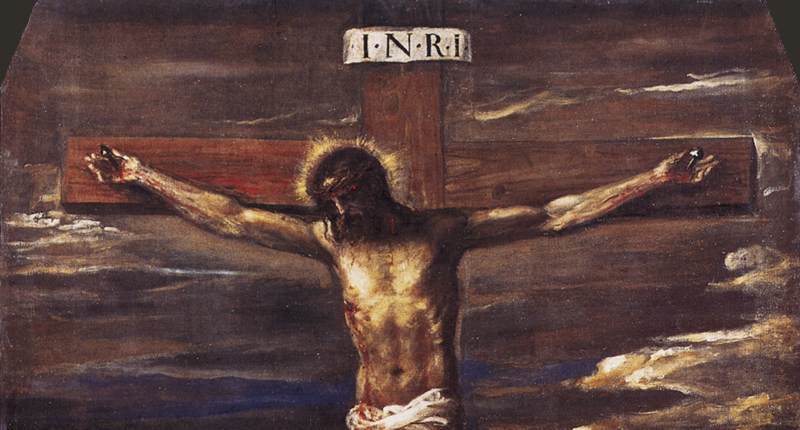

From this we can draw a further conclusion. We have seen that the teaching contained in today’s Gospel isn’t a moral teaching in the sense we have indicated. But more than that, it isn’t a teaching primarily about us at all. Instead it is a teaching about God: more precisely, about the Divine life in which we are called to share. We can think of this from several related perspectives. We can say, for example, that our Lord is here giving us a self-portrait. In this self-portrait His own redemptive self-emptying is anticipated and clarified. But we can also say that His redemptive self-emptying reflects a pattern of self-giving which is not only in the Incarnate Word. Preeminently, mysteriously, it pre-exists among the Persons of the Blessed Trinity themselves.

That, however, takes us beyond the immediate scope of today’s Gospel, and would be a meditation for another day.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.