02 Dec Reflections on the Coming of Salvation

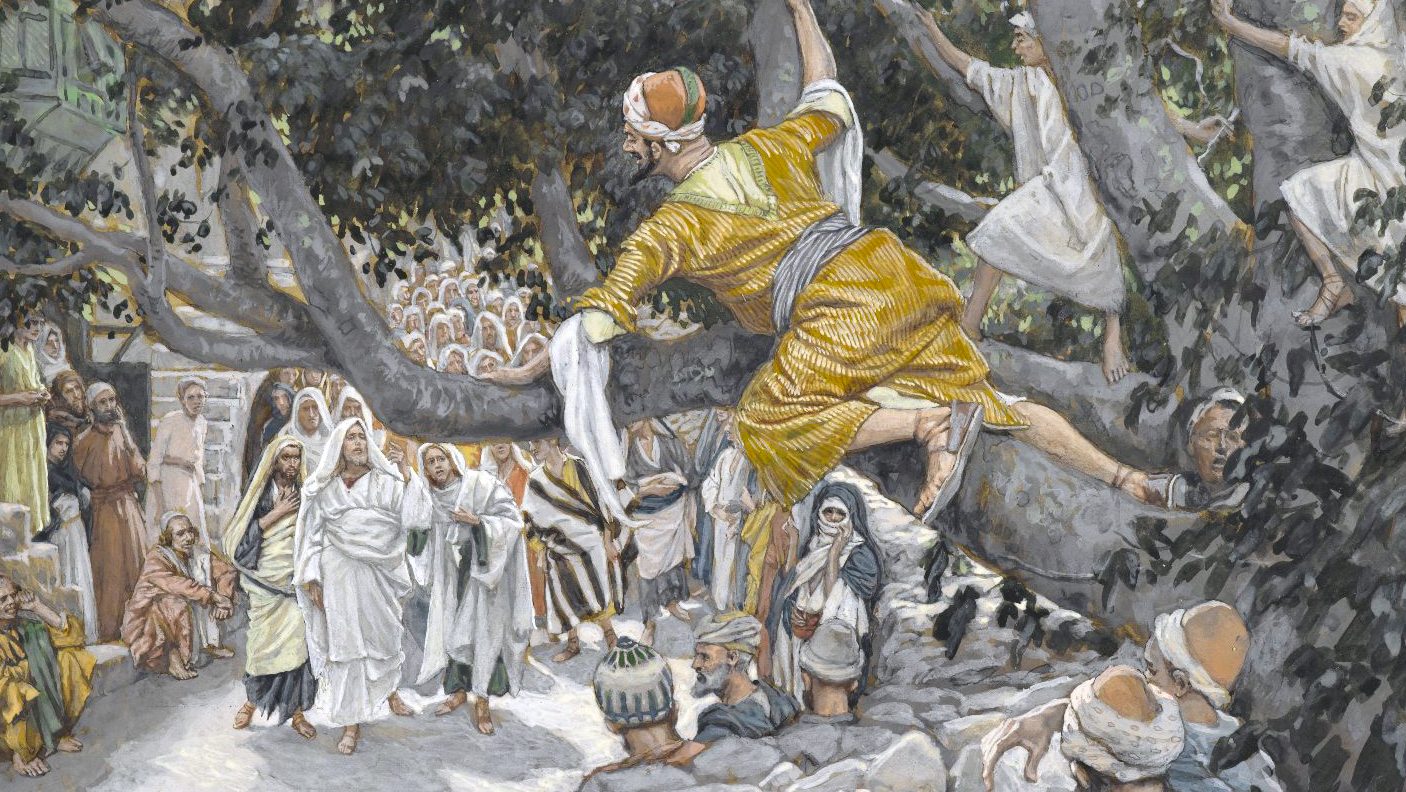

Zacchaeus, conscious of being too small to see, runs on ahead and climbs a sycamore tree so as to be able to catch a glimpse of Jesus as He passes by. Zacchaeus is seized by curiosity, and raises himself up to satisfy it. And so he changes where he stands, but only physically, not spiritually or morally: he acts impulsively and confidently, running and climbing, remaining exactly as he is – a chief tax collector and rich – and tries on his own initiative to grasp what would otherwise be inaccessible to him. If we think for a moment of the end of this account in the Gospel, we find Zacchaeus changed in a different way: he is back on the ground, the movement of raising himself up reversed, and in its place we find another kind of change, an interior difference: we see him undergoing a conversion, repentant and at the same time self-forgetful: Behold, Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor; and if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I restore it fourfold. But when we first encounter him, all that is still to come. At the beginning, Zacchaeus is merely asserting himself and engineering by his own resources what will satisfy him. He starts off, in other words, with the same attitude towards Jesus that he has towards everything else: the very same disposition that has brought him professional success and personal enrichment is what drives him to climb the sycamore tree and make of Jesus an object that will fulfill his curiosity.

And yet of course we have also to say that, even at the beginning, something good is stirring in Zacchaeus, something has touched him, even if at a level which awaits deepening. Zacchaeus might, after all, have remained indifferent to Jesus, or distracted from Him; but instead Zacchaeus intends to encounter Him somehow, make contact, even if it is only on his own terms and for his own purposes. This is already a grace responded to, even if the response is as yet narrow-minded and constrained, caught up in Zacchaeus’ existing sense of himself and not yet released to effect the transformation which grace always has in view. And of course this is how it is, not only with Zacchaeus but also with ourselves. Grace is always being offered us, and even when we don’t turn away altogether, even when we find a way of receiving it, still our reception is typically limited, conformed as far as we can manage to our present way of being, and resistant to the deeper changes which God seeks to effect in us. God gives Himself to us, and yet we hold ourselves in reserve, asserting ourselves and our own interests and taking from grace only what we are prepared to grant it. And yet, for all that, grace perseveres in us: it persists in inhabiting our pride and half-heartedness, our self-interested calculations, and without ever giving up awaits from us a better and deeper generosity.

Compared to the grace which is offered us, we like Zacchaeus are small of stature: miniature recipients of a treasure that always exceeds us. And like Zacchaeus we want to be taller, larger, more comprehending; but we want to achieve this for ourselves, again like Zacchaeus, running and climbing, asserting ourselves and elevating ourselves so that even God can be brought under our control. It is this which somehow has to be reversed in us, undone, so that a counter-movement can come to life, a deeper receptivity in which we do not try to shape grace but instead allow grace to shape us, letting down the barriers of self-preservation and giving way, finding ourselves surrendered to God’s will and not enslaved to our own. Like Zacchaeus we must be induced to stop climbing, we must allow ourselves to be brought down to earth, being moved and sustained not by ourselves but by God.

And so Jesus says to us, as He says to Zacchaeus: come down, for I must stay at your house today. The movement of coming down is an essential precondition of the promised intimacy: God cannot dwell with us until we have descended from the heights of our proud self-determination. The encounter that we wish to produce and control for ourselves is something which only God can give, and for this we have to allow ourselves to be within reach.

Our descent mirrors God’s own descent, our letting go of self-preservation and self-command brings to life in us our most fundamental likeness to God’s own way of being. When the Eternal Son descends to us in the Incarnation, He does not cease to be God in order to become man: on the contrary, in descending to our condition He remains Divine, in fact preeminently so, and thereby shows us Who God is: we are shown that God does not cling to Himself, but goes out of Himself, humbling Himself, casting Himself into the condition of those far removed from Him, in order to find them where they are and draw them back to Him and to themselves. God is intrinsically this descent of Love. And so when we descend, when we are prepared to surrender ourselves for the sake of others, we are sharing in God’s own movement and life, and therefore also finding or re-finding ourselves, not by self-assertion but by self-forgetfulness, re-identifying with our deepest origins in the Divine Love which brings us into being and sustains us.

But this revelation of the God Who descends inescapably troubles us. Because the movement of self-assertion is so strong in us, we most naturally form images of God which repeat and confirm that movement: our instinct is to think of God as almighty, powerful and royal, ruling, rewarding and punishing like a worldly monarch; and this in turn means that we see God as one Whom we must flatter and serve in order to try to ensure that we are on the winning side. And so when the God Who descends unsettles this way of thinking, we find it easy to be scandalized, exactly like those who murmur against Jesus: He has gone in to be the guest of a man who is a sinner. In our hearts we find ourselves wanting another god, a god who will vindicate our pride and self-assurance, not One Who sides with the outcasts. We seek a god to raise ourselves up, not one Who throws Himself into the human depths. And yet the Gospel refuses to allow us the luxury of a god made according to our own image. We do not find God on the heights that we imagine and create for ourselves. We find Him only in the poverty of the human condition, a condition from which, desiring to relinquish our pride, we are no longer determined to flee. Those who murmured against Jesus murmur also against Zacchaeus, because they are in flight from what it means to be human, insisting on their own eminence and despising and condemning those whom they identify as outsiders. But what Jesus shows is that in God’e eyes there are no outsiders – unless we all are: since, as He says, Zacchaeus also is a son of Abraham. And because the Son of man came to seek and save the lost, we must be prepared to find Him only there, and so in the acknowledgment that we are indeed lost, helpless and incapable – not winners but losers – accepting our solidarity with the outcasts whom God Himself has befriended so as to teach us to do the same.

Somewhere between his descent from the sycamore tree and his repentance in the midst of the intimacy that Jesus has accorded him, Zacchaeus begins to realize this and to allow it to act upon him. He no longer desires to run and climb, but only to be held and handled by Love. For this reason, and only for this reason, Jesus says that today salvation has come to this house.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.