03 May Reflections on the Claims of Christ

Who do you claim to be?

I think we are right to hear a certain reserve, even discomfort, in the way Christ answers this question. It is as if such interrogation – who do you claim to be? – invites Him to make a kind of declaration about Himself that He would otherwise desire altogether to avoid.

What indeed can He say to them?

If I glorify myself, my glory is nothing; it is my Father who glorifies me, of whom you say that he is your God. But you have not known him; I know him. If I said, I do not know him, I should be a liar like you; but I do know him and I keep his word.

It seems to me that to try to hear these tangled affirmations and denials as being spoken self-confidently, even self-assertively, puts them under pressure, forcing them into a shape that distorts them. We do better to hear in them a kind of unease, even anguish – the kind that comes upon us when we are compelled to speak about what cannot be articulated, but only lived and exemplified.

For Christ does not wish to speak of Himself, to ‘seek His own glory’ or to ‘glorify Himself’: to do so would undermine the whole truth He wishes to convey, plunging everything into the nothingness of mere self-possession. The ‘word’ that He calls His own is not His, but is given Him against the grain of possession, handed over to Him only so that He can hand it on. It is a word framed by a Father for His children, mediated by a Son as Light and Life, the refraction of an Infinite belonging into the estranged finitude of creation.

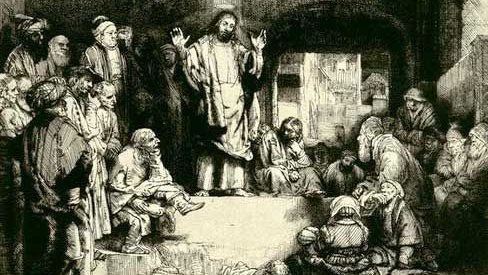

And yet the Pharisees – so confident of possessing themselves, appealing to the religious tradition of Abraham and the prophets of which they take themselves to be the privileged guardians and interpreters – the Pharisees, in their stubborn resistance, draw Him into trying to do what seems impossible. What seems impossible here is saying ‘I’ although He means ‘we’, pointing to Himself when the One to Whom He desires to point, the One Whom He wishes to render visible, is not Himself, but the Father: the Father Who desires only to gather them all to Himself, Christ and the Pharisees together, into the generative Trinitarian companionship by which creation is fulfilled.

It is as if Christ wants to say: Look, can’t you see, I am nothing in myself. In so far as there is anything to see, when you see me, it is a matter of seeing with me and therefore beyond me, to the One Whom I strive to honour simply by bringing you to Him. Don’t ask me to advance claims on my own behalf – if I make claims, it is only to point away from myself, either towards the Father, in one way, or towards yourselves, in another: it is to show you, despite your refusal, that you yourselves can stand where I stand, and see what I see, that we can stand and see together, all of us turned in the same direction, towards the Father Who undertakes to glorify all that He has made.

This is the transparency which makes trying to explain it so cumbersome, almost self-defeating. If explanation is somehow required, this is only because of the distance from Christ which the Pharisees take up, their refusal of the companionship with Himself that He offers them as children of the Father. It is this, and only this, that compels Him to risk insisting upon Himself, speaking of what He knows and of the glory that is His.

For in truth His whole reason for being tends in the other direction. Imposing Himself between them and the Father, placing Himself over and against them so as to insist upon a space reserved to Him alone – all this is the exact opposite of what He desires. If this is nonetheless what seems to happen, it is the Pharisees who require it, by refusing to move from their own place to the place where He Himself stands. And unlike them, He does not stand there oppositionally, as if this were His place as distinct from theirs; He occupies His place for the sole reason that He desires to share it with them, making of it a common space of affinity, received from the Father and offered back to Him. Refusing this pays Him the dishonour of which He speaks, not by denying His exclusivity but precisely by insisting on it. And then, by styling Him a sinner, a Samaritan and a demoniac, they reinforce the opposition that resists His purpose, holding Him at the distance which only a lie can sustain.

In doing this, by refusing to stand in the place which He offers them – the place which is theirs because it is His – they consign Him to an isolation that He doesn’t seek and which it is His whole purpose to overcome. His one and unbroken impetus is to offer them the gift of being a child of God, not holding on to it Himself but instead inaugurating its universal diffusion. And yet it turns out that He is the only one prepared actually to receive this gift, to allow it to flow into Him unreservedly, enacting in everything that is given Him an acknowledgment of the Father’s encompassing Love. The others, He finds, want to stand apart, insisting on God, of course, but refusing the Father. And since God is none other than the Father, their refusal to be children means a refusal even of the God they would cling to, Whom they call their own; because they refuse this, they refuse God Himself, for there is no other way of relating to God than in the expressive intimacy existing between parents and children, a language which they will not inhabit because they refuse to find themselves once more in the One Who originates them.

And so the One Who, uniquely, knows Himself as a Child of the Father is made to stand alone, to speak of this relation as if it existed in splendid isolation, a kind of sacred exchange revealed so as to evoke, at best, respectful veneration at a distance, but more typically, as with the Pharisees, suspicion and repudiation. Nothing could be more mistaken. Here the refusal to accept what He offers means driving Him into hiding. But soon enough that refusal will strip Him of all possibility of seclusion, and on the Cross will break Him open in His fidelity to surpassing it.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.