31 Jul Black-line

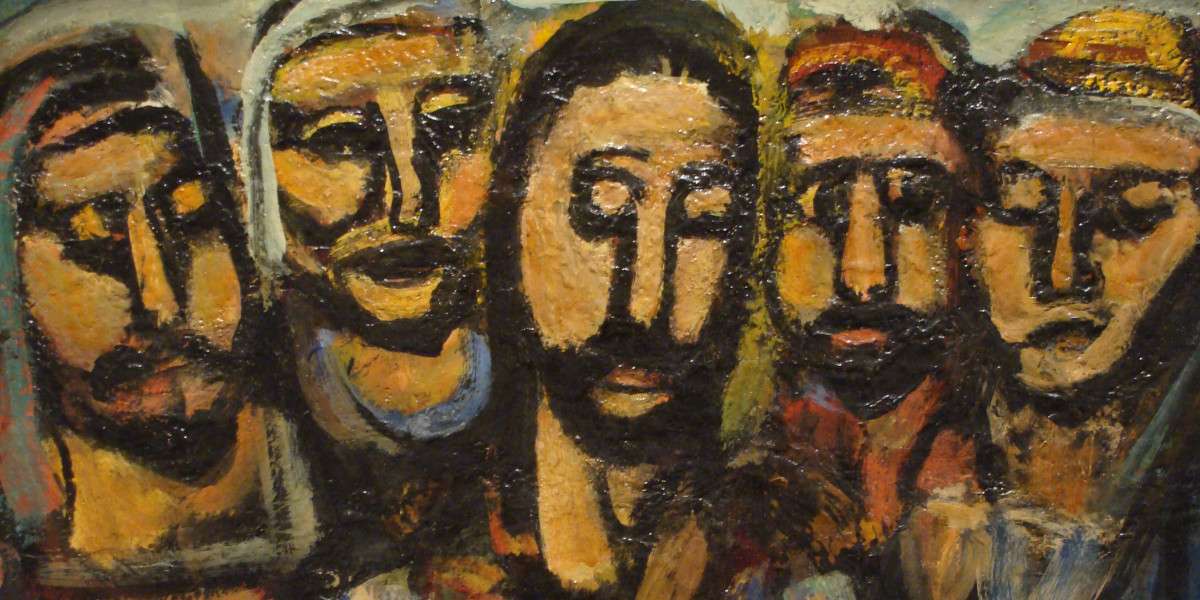

The delight I take in the prints and paintings of Georges Rouault, is either too hard to explain, or too easy. Currently I wake each morning to Christ and the Apostles. Not the painting itself, which I understand belongs to some collector in the Distrito Federal of Mexico; mine is a large detail from the cloth cover of a cheap art book, published in the ’sixties. The shiny viscose coating peeled off, and the matt effect from the cloth ground makes it look like a frameless painting once again — not the visual confection we have come to demand in our “coffee table” books. And of course, there is no smiling in this composition, as there also is not on the Crucifix nailed into the white plaster, a few feet to the left. Nor on the peasant wood carving of a chalice-bearing Saint John, at my right shoulder as I rise — from my narrow, hard-plank, wrought-iron cot, rescued from a defunct Dominican monastery.

I am not very holy. Perhaps I arranged these things in the hope I might become more so. The High Doganate is not otherwise much dripping with Catholic impedimenta, thanks perhaps to my earlier immersion in Anglican “good taste,” and something of Bauhaus modernism before that. I have an allergy to sentiment, and imagery that is “soft.” Girlishness is for girls, in my non-negotiable opinion, and especially today, our hapless need cries out for religious art that is Christ-ish and masculine. This includes representations of Our Lady that are feminine, in an adult way: womanish not girlish.

It is true that Rouault apprenticed in the shop of a stained-glass restorer, and his work seems obviously to emerge from that conception of lead outline and tinted glass. Were that all, it would be a decorative nothing. Instead, Rouault has penetrated the surface of his effects, to what lies beneath or behind or is philosophically prior to the lighting of the great Cathedrals. He is, as it were, “edgy” in an heroically pre-modern way, that is also pre-Gothic.

Generations before the Lindisfarne Gospels, or the Book of Kells we have (and by some miracle still have, in Dublin) the Book of Durrow. A product of seventh-century “Celtic” monasticism in Ireland or Northumbria, it is ambassador from what we call the Dark Ages. I read subtle, post-Christian condescension into most art-historical accounts of it, sometimes abrogated by a sudden amazement. For it is not primitive work, and in its coloured patterns within vibrantly delineated fields, it presents the Gospels as we can no longer read them: without the slightest hint of what we would now call “romanticism.” The “carpet pages” are not frills; they pass intentionally across thresholds of our human understanding, into an unearthly geometrical abstraction.

Christ stands in the interstice of here and hereafter, as the Gate of Revelation; and the Man of Matthew, the Lion of Mark, the Ox of Luke, and Eagle of John, are hardly copied from nature. Our religion carries us from this world, into the face of Eternity, and the iconography by which this is conveyed looks not wistfully back. Sanctity does not do so, and the artists — to whom it never occurred to sign their work for commerce — are themselves involved in an activity that is solemn and liturgical. Humour they had, but never jokiness; gentleness and compassion but in a form we might call hard, for founded in Love not Pity. The illumination of this codex, the uncial, majuscule lettering, is itself, though wildly beautiful, hard and immovably bold, as if carved or engraved beneath the ink. The gold is enhanced in jewelled settings of a recurring, mystical earth red — the colour of dried blood.

Long, long before the outburst of stained glass in the High Middle Ages — in far insular West as in far Byzantine East — we had art which purposefully ignored anatomical modelling, foreshortening and perspective (they are different things), the dynamism of flow and movement; which was unrolled, flat; crystalline, rather than rounded and organic in its aspirations. It stands so opposed to our temper as to expose us for the “naturalistic” animals that we are.

I write this as gloss on my review of what may be the height of post-modern art, in another essay (over here). Compare, if reader will, the black-line of our ancient Christian icons and frescoes and manuscripts, to what perfectly expresses our own techno-logic heart and soul: the aspiring naturalism of the sex robot.

By David Warren, lecturer in religion and literature, St Philip’s Seminary