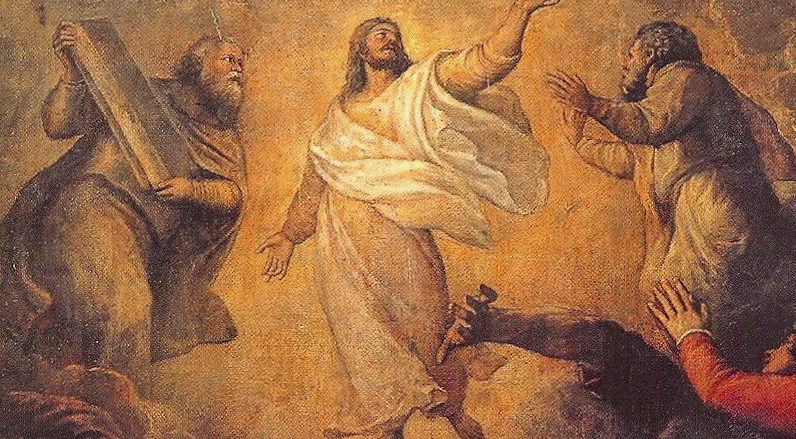

09 Aug Reflections on the Transfiguration of Christ

The Lord … made that form of His body which He shares with other men to shine with such splendour that His face was as bright as the sun, and His clothes became as white as snow. By changing His appearance in this way He chiefly wished to prevent His disciples from feeling scandalized in their hearts by the cross. He did not want the disgrace of the passion …

to break their faith. This is why He revealed to them the excellence of His hidden dignity. In these words St Leo the Great unfolds the mystery of the Transfiguration: Peter and James and John are offered a vision of glory meant to sustain them in the suffering to come. In other words, Leo interprets glory as mercy, an elevation that discloses itself only in reaching down so as to raise up, a splendour wholly attuned by its tender comprehension of the fragility of our capacity to endure. Even in this dazzling manifestation God does not want to impose Himself, but instead anticipates and solicits us, refusing to exceed vulnerability to our waywardness. And we know that Divine vulnerability is not merely theoretical. The sequel to the Transfiguration includes repudiation and betrayal; at the foot of the Cross, only John remains.

We must resist the thought that this means that the grace of the Transfiguration, as St Leo interprets it, ended in failure. Grace does not fail us, when we turn from it; in turning from it, it is we who fail grace. It is true that Christian theology has sometimes entertained the notion of irresistible grace, grace which determines our very acceptance of it, but the Church teaches against this idea and in truth there is no such thing. Grace does not determine us; under grace, we determine ourselves. Nothing can be done without it, everything depends upon it, but there’s a difference between being dependent and being compelled. Not even the Transfiguration compelled.

But why not? St Leo’s commentary perhaps provides us with some clues.

He emphasizes the elements of scandal and disgrace which circulate darkly and potently around Christ and His Cross. In their hearts, St Leo tells us, Christ desired His disciples to be able to enter into these things and live through them.

In their hearts – the place of their deepest, most defining desires. What was it, when they witnessed the Transfiguration, that the disciples most deeply desired?

At one level, who can say? But following St Leo’s suggestion, we can at least suppose that what Peter and James did not want was the path that would unfold itself in the scandal and disgrace of the Cross. More precisely, they would find themselves actively refusing any path which demanded such things. They would, in other words, do anything to avoid the marginalization, dispossession and defeat which Christ and His Cross required them to endure.

They imagined they knew the kind of Saviour, and therefore the kind of salvation, which they were being offered. They looked to Christ for the fulfilment of their fantasy of enjoying a dramatic and decisive vindication, a glorious overthrowing of the alien and Godless people who dominated and despised them. And as they watched this fantasy evaporate, as they saw the path ahead requiring of them not abundance but renunciation, an intensification of vulnerability and abjection, then we find that they could not, in fact would not, embrace it.

Perhaps what Leo calls the ‘hidden dignity’ which Peter and James had seen disclosed in the Transfiguration perversely strengthened their refusal. For hadn’t they seen, precisely in that dazzling ‘hidden dignity’, the promise of a glory which would undoubtedly be theirs? And yet, in what followed upon it, their hold upon that glory receded, apparently irretrievably. If they recalled the grace of the Transfiguration, perhaps they felt taunted by it, even, themselves, betrayed. When we feel betrayed we do sometimes, and even violently, reject the ideals and desires which once upon a time had animated us. Can we glimpse this perhaps in Peter’s repudiation of Christ following His arrest? Three times Peter has to face the question: Are you not one of his disciples? And in response, cursing and swearing as St Mark tells us, Peter insists I do not know this man of whom you speak. In this, there may be more than fear at work.

But whatever the truth of this, if we turn from Peter to John, we can ask: what did John have, that Peter lacked? What enabled John, at the foot of the Cross, to see that this was not the betrayal of what the Transfiguration had disclosed, but in fact the passage to its fulfilment?

John is traditionally seen as the embodiment of the contemplative spirit, in contrast to Peter’s impulsiveness, his yearning for action and palpable achievement. And relatedly, John’s affinity is for love, for love as the meaning of God and of all that God does, the meaning of all that God undergoes, of all that He suffers on our behalf and therefore at our hands. Is it perhaps this which enables John to persevere? Is it this that makes him uniquely attuned not to victory, which the defeat of the Cross cannot, as such, disclose, but rather to love and its consummation, the consummatum est – It is Finished – which, in John’s own Gospel, is Christ’s final and definitive Word from the Cross?

St John, perhaps, possessed a special insight into God. It was an insight nurtured in contemplation, in his adherence ultimately only to love and love’s demands. Uniquely among the Evangelists, it is John who insists that the deepest and truest name for God is nothing other than Love. Surely it is this which enabled him to see what Peter refused to see. The ‘hidden dignity’ of which St Leo speaks, momentarily disclosed in the Transfiguration, is according to the speculative affinity of love not contradicted by the Cross. On the contrary, the Cross is in fact a disclosure of the very same glory.

John’s Gospel alone records the words Christ spoke in imminent anticipation of what He calls His hour, that is, the time of His suffering and death. ‘Father‘, He prays, ‘the hour has come; glorify thy Son that the Son may glorify thee‘. And God’s glory is not divided: this is the same glory as was disclosed at the Transfiguration, but disclosed at a new angle, from a new perspective.

And perhaps the angle from the Cross is wider, the perspective deeper. Even in the unveiling of glory in the Transfiguration, something remained hidden, or at least ambiguous. What remained ambiguous was the insight the Transfiguration offered into how the glory of God is to be interpreted. What was in fact disclosed was, at the deepest level, the glory of Divine love. But for that disclosure to be completed, the Divine self-abasement, which St Leo sees as already implied in the vulnerability of the Transfiguration’s condescension to our waywardness, had to be rendered as unmistakable as it can be. What the descent lying at the heart of Divine glory actually looks like remains, in the Transfiguration, imperfectly expressed. It fulfills itself only on the Cross. Only then are we permitted to see, as visibly as the mystery allows, the ecstasy of love that the Transfiguration had begun to reveal. Only on the Cross does glory clarify itself as charity.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.