01 Sep Kurelek: The Journey to Faith

[Note: This essay is basically an extraction of interesting elements from the first portion of Kurelek, A Biography (1986) by Patricia Morley].

Hailstorm in Alberta

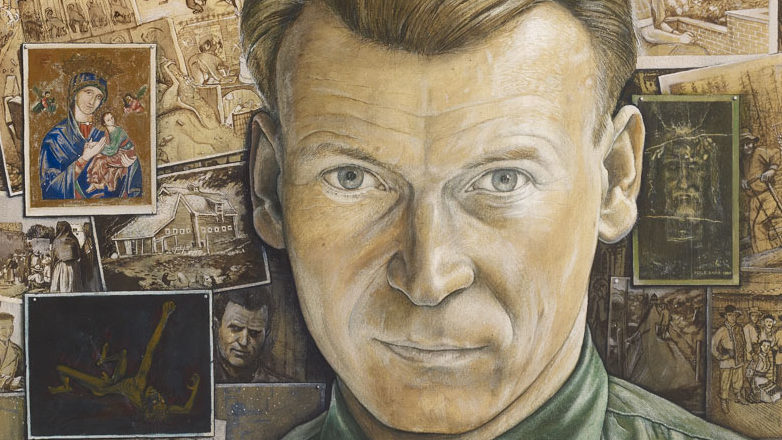

Bill Kurelek was born in 1927 to Ukrainian pioneers who had settled near Edmonton, Alberta. Journalists dubbed him “the people’s painter”, but he was respected by influential figures in the art scene of North America in the 1960s and 1970s, notably by his Toronto dealer, Av Isaacs, and by Alfred Barr, the director of collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in NYC. The latter selected a Kurelek picture called “Hailstorm in Alberta”, 1961 over contemporaneous Canadian abstract paintings when, in 1961, the Women’s Committee of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) invited Barr to Toronto to choose a work of art for the MOMA collection. Toronto’s art aficionados were astonished.

A Prairie Boy’s Winter

Notwithstanding this idyllic scene, “Prairie Boy’s Winter”, 1973 Kurelek did not enjoy his childhood. He was the eldest of seven, he was sensitive, and his father was a harsh taskmaster. His brother John, 20 months younger, was everything that Kurelek was not: mechanically gifted, a huge asset to the family farm, and gregarious. This caused Kurelek to retreat into a silent shell from which he later only gradually emerged through his pictures and the extensive written verbiage which often accompanied them. In psychological terms, there was no “goodness of fit” between Kurelek and his father. Kurelek later described his emotional state as that of depersonalization, a state of extreme anxiety in which a person experiences a change in self-awareness, which might include feeling as if one’s thoughts and actions are not one’s own, perhaps as far as experiencing the sensation of watching oneself from the outside.

The father may have been harsh, but his harshness promoted a strong work ethic which caused the Kureleks to prosper in spite of the destruction of their first home by fire (all the icons burned and Kurelek’s parents never replaced them), and the agricultural depression of the 1930s. They were able to buy a dairy farm near Winnipeg to which they moved when Kurelek was seven years old. When the three eldest were teen-agers, the parents bought a house in Winnipeg so that the children could live there alone and attend high school. This placed Kurelek in the orbit of an Orthodox priest, Fr Mayevsky, who was a Ukrainian nationalist. He recognized Kurelek’s artistic talent, gave him artwork to do for the church, and spoke to Kurelek’s reluctant father to defend the son’s ambition to become an artist.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

The Ukrainian Orthodox phase was short-lived when Kurelek came under the influence of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1950, and of Irving Stone’s biography of Vincent Van Gogh, Lust for Life. In his own terms, he became a “leftist rebel against society” as he obtained his Bachelor of Arts (1949) from the University of Winnipeg, majoring in Latin, English and History. He later described his time at university as an emersion in the spirit of “secular humanism”. In the painting “Harvest of Our Mere Humanism Years”, 1973, Kurelek depicted the university system as an empty shell, a grasshopper eaten by ants who represent students in search of meaning and satisfaction.

Harvest of Our Mere Humanism Years

Having been introduced to the European tradition of painting by a fine arts history course, Kurelek enrolled in the Ontario College of Art (OCA) in Toronto where he spent a mere one year under the tutelage of several instructors, including one Eric Freifeld, who as drawing master was his chief influence. Much later Freifeld described Kurelek: “He wasn’t worldly… He was a little like a figure out of Dostoyevsky, cryptic and mysterious…He identified with Dostoyevsky’s protagonists.”

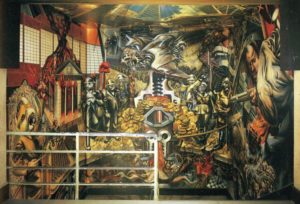

Sequieros

Kurelek next set out for Mexico with a view to studying under the muralists, such as Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros. He lived rough but managed to visit galleries in California. While on the Arizona desert he tried to sleep in a culvert, and in the freezing cold was visited by an apparition whom he termed “someone”. The “someone” was clothed in a long white robe and said, “Get up; we must look after the sheep or you will freeze to death”. As he got up, the sheep became clouds and the “someone” blended into him and was gone. Kurelek later chose as the title for his autobiography Someone with Me, which was published in the early 1970s. He spent just six months in Mexico, studying at the Institudo Allende where the chief instructors were not Mexican muralists. While there, he discovered a book, The Natural Way to Draw by Kimon Nicoleides which he later studied and credited as being his main teacher.

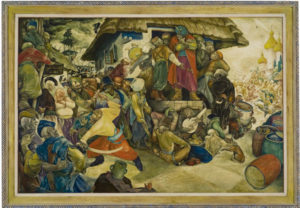

Zaorozhian Cossacks

Upon returning to Canada, Kurelek visited his family and painted an enormous illustration of Gogol’s Taras Bulba which is titled “Zaporozhian Cossacks”, 1952. He also worked in a lumber camp, earning $1800 to travel to Europe. As he awaited passage on a Cunard cargo ship, he lived in Montreal on a diet of bread, margarine, grapefruit and cold pea soup. He applied to take lessons at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, which he termed “that beautiful asylum for the elite”, but was turned down. He read Orwell’s 1984 and wrote to his communist friends at OCA recommending it, only to discover that his letter produced a termination of their friendship.

Zacharias and Elizabeth by Spencer

Kurelek embarked for England in May 1952. Four days off the boat, he went to the doors of the Maudsley, then and now England’s premiere psychiatric institution. The doctors found him interesting, and secured for him temporary lodging as he awaited a bed at the hospital. He was assessed as being “severely ill”, but, contrary to some Canadian ‘folklore’ about Kurelek, none of the UK doctors ever considered that he was suffering from Schizophrenia. His attending psychiatrist described Kurelek as a man “with a very introverted personality, a shy man, with periods of depression”. Kurelek was admitted to Ward Four, where he found the atmosphere to be comparable to the camaraderie of a lumber camp.

Tondal’s Vision by Bosch

When the doctors discovered Kurelek’s artistic ability, they sent a few of his pictures to a certain Golf Rieser, who affirmed his talent but declared that he should not go back to art school. His attending psychiatrist also wrote to Stanley Spencer because Kurelek admired his work. Spencer wrote back and offered to meet Kurelek, but the meeting did not take place, perhaps on account of Spencer’s illness.

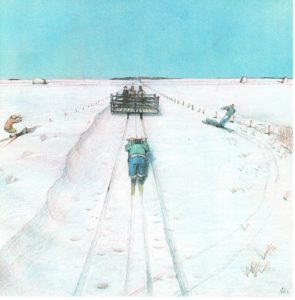

It appears that they did not lock you up and throw away the key on Ward Four! In August of 1952 Kurelek travelled to the continent to look directly at his favourite masters: Bosch and Brueghel and the Van Eyck altarpiece. Perhaps this was part of his therapy. After he failed to get into an art school in Paris, he returned to London to work as a labourer for the London Transit Commission. He painted “Tramlines”, 1952 which sold right away for 30 guineas.

The Triumph of Death by Brueghel

Tramlines

Margaret Smith

Nonetheless, Kurelek remained a psychiatric outpatient under the watchful gaze of the National Health Service. He created nightmarish drawings which inspired fear in his doctor, Bruno Cormier, a Quebecois who had recently been a co-signatory to the “Refus Global”, 1948. These drawings depict helpless victims juxtaposed with rapacious male figures: for example, a man buried to his shoulders endures a monstrous bird pecking out his eyes with one claw, as his mouth is held shut by the other. One doctor thought that Kurelek exaggerated horrors in a melodramatic way, which is actually a characteristic of depressed patients.

Nightmare

But was Kurelek truly mentally ill upon admission to the Maudsley? He later wrote, “I was play-acting the role of a patient in the hope of effecting a break-through”. His biographer notes that even while under their care, Kurelek told his doctors that he was acting a part. What is clear is that he was extremely introverted, which led the Maudsley doctors to assign him an occupational therapist by the name of Margaret Smith. She was given the task of socialising Kurelek. When she discovered that they both enjoyed poetry, she gave him an anthology of English verse wrapped in a Catholic newspaper! Kurelek then discovered that Miss Smith, a Catholic, had been praying for him.

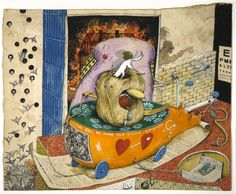

The Maze

Around this time, Kurelek painted “Nightmare” and “The Maze”. Here is an excerpt from Kurelek’s own account of “The Maze”: “The thorny, stony ground is a kind of T.S. Eliot Wasteland, spiritual and cultural barrenness, the pile of excrement with flies on it represents my view of the world and the people that live on it. The loosened red ribbon bound together the head of a kind of T.S. Eliot Hollow Man and was untied by psychotherapy (Dr Cormier) but since the outside world is still unappealing the rat remains inert…”

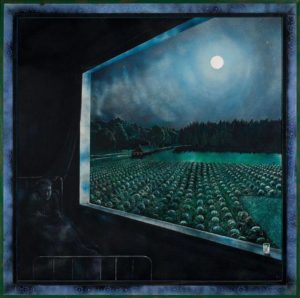

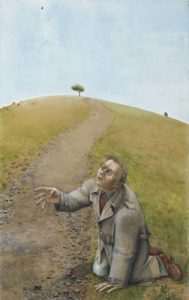

All Things Betray Thee

Once again the doctors sought expert art advice, this time from Sir William Coldstream, a realist painter who was principal of the Slade and an art world poobah in the 1950s. Coldstream admired Kurelek’s draftsmanship, but declared that his work was lacking in originality and colour sense. And so in 1953 Kurelek, perhaps feeling demoted as painter and patient, was dismissed from the Maudsley and sent to Netherne Hospital, this institution chosen on account of its art therapy programme led by Edward Adamson. Ensconced in one of Netherne’s residences, Highfield Villa, which was surrounded by a cabbage patch, Kurelek underwent a mystical experience. He woke up one night to find the moon shining brightly on the cabbage field. All was peaceful, yet, as he recalled, he experienced “a sense of complete and utter abandonment”. But thinking of Margaret Smith, Kurelek began to pray for the first time since he was eleven. Many years later he depicted this experience in the painting “All Things Betray Thee Who Betrayest Thee”, 1970, this line taken from Francis Thompson’s poem, “The Hound of Heaven”, 1893.

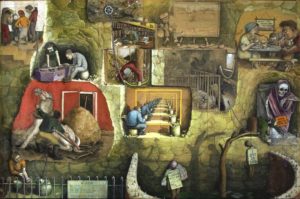

I Spit on Life

At Netherne, Kurelek enjoyed the encouragement of his art by Adamson, but endured the psychotherapeutic approach of one Dr Sybil Yates who, having traced his troubles back to babyhood, told him to construct a baby out of plastiscene and to carry it around wherever he went. This plastiscene doll later grew into a paper doll and finally, a two-foot wooden puppet. At this time, his lowest point psychologically, he painted “I Spit on Life”, another maze-like painting in which Kurelek family scenes, self-portraits and chambers of the mind are presented, with a prevailing theme of entrapment and death. ‘Willie the Christian Clown’, chained at the ankles, makes an appearance, and there is a billboard proclaiming, ‘Come to Church’!

Other paintings from this period are:

“Where Am I? Who Am I? Why Am I?” in which the face is indebted to Brueghel’s blind men.

Where am I? Who am I? Why am I?

“The Ball of Twine and Other Nonsense”, 1956;

The Ball of Twine and Other Nonsense

and “Lord that I May See”, 1955.

Lord that I May See

Kurelek later reflected that painting at Netherne had not helped him: “No matter how intensely I painted out my accumulated store of fears, hates and disillusionments, they still remained with me as an immense psychological burden”. When interviewed by Kurelek’s biographer in the 1980s, Adamson disagreed, asserting that painting had externalized Kurelek’s aggressive feelings, while allowing that painting could intensify violent feelings rather than alleviate them.

In any event, after 18 months of painting, Kurelek attempted to kill himself by ingesting eight sleeping tablets and inflicting numerous cuts with a new razor. At the same time, his painting activity had declined dramatically from ten hours to two hours per day. Margaret Smith later observed that he had deteriorated while at Netherne. The doctors abruptly ended the psychotherapy and recommended electric shock treatments (ECT). Kurelek consented. Adamson, the art therapist, thought the practice barbaric, but it was the most effective treatment available at the time – and still is if you are severely depressed.

Kurelek compared the shock treatments to the Spanish Inquisition. Yet in this ordeal, Kurelek reflected that he found ‘Someone’ with him. He commented: “It is said that sorrow remarries us to God and how true that is. Here was an experience horrendous enough to knock the cocky self-sufficiency out of any man. One prays best when one is really and helplessly up against it. That is when I, too, resumed prayers. I’ve been praying ever since.” But there was a second factor in play. Because Kurelek had received his first treatment without muscle relaxant, his back was wrenched from the shock, and he was moved to a convalescent ward where the ‘incurables’ lived. He recalled that, beholding their pathetic condition, “for the first time in my life I was touched with pity, real pity for someone besides myself”. Morley, his biographer, observes that he had breached the wall that had previously separated him from other human beings.

Interestingly, even though Kurelek compared the experience of the shock therapy to the Inquisition, he gave more credit to these treatments than to anything else at Netherne. He said, “I must consider my suicide attempt in some ways fortunate, if only for the ECTs and the blessed relief they afforded me from the crushing load I’d carried all those years. In my case they really worked.”

Kurelek discharged himself from Netherne in late 1954, and supported himself by painting and selling trompe l’oeils which were shown at summer exhibitions at the Royal Academy. Moving towards the Catholic Faith, he frequently attended Mass at the Brompton Oratory, accompanied by his art therapist, Adamson. He also visited the Tate, where he would have seen Stanley Spencer’s New Testament scenes set in Cookham, and the National Gallery, where he was entranced by an exhibit of Brueghels which included the “The Mocking of Christ”. He joined the Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen. He became the friend of a sculptor named David John who belonged to a group of Catholics called “The Cell”. In this milieu not only did Kurelek’s religious convictions begin to take shape, his outlook as an artist coalesced: he came to regard artists as craftsmen, to hold that tradition is more important than innovation, and to affirm that art exists to glorify God.

In 1955 Kurelek undertook a correspondence course with the Catholic Enquiry Centre, started attending Mass regularly (he found this boring), read Alfred Noye’s The Unknown God, (1934) and went on pilgrimage to Lourdes. He was assigned a spiritual director who was incompatible because he reminded Kurelek of his own father. Nonetheless, Kurelek went regularly to pray at a church called St Simon and St Jude in South London where he met the priest, Fr Thomas Lynch, who turned out to be more of a kindred spirit. Fr Lynch commissioned Kurelek to paint portraits of the church’s patron saints and a crucifix, which illusionistically looked like wrought iron. Around this time Kurelek also tentatively proposed marriage to Margaret Smith, who turned him down. He was relieved to discover he was still desirous of the Faith in spite of being refused!

While Kurelek was attracted to the Church, he nonetheless faced some difficulties in relation to the existence of God! He was therefore brought by Father Lynch to meet with the theologian, Father Holloway, later author of Catholicism: A New Synthesis (1969). Kurelek’s biographer observes that both Holloway and Kurelek shared the prophet Jeremiah as their inspiration. Also, the biographer asserts that Holloway was strongly critical of our decadent and materialistic society, and that Kurelek was very much influenced by Holloway’s stance. Holloway found Kurelek “rational as a scientist, yet mystical”.

Kurelek was conditionally baptised on the feast day of Our Lady of Lourdes in 1957 with Margaret Smith serving as a godparent. He declared, “I’d arrived home at last. Now I could start living”. Living for Kurelek meant painting what he termed “religious propaganda”. Inspired quite directly by the command from the apparition beheld in the Arizona desert back in 1947, he embarked upon completing 2000 works during the 17 years remaining to him. As Kurelek stated towards the end of his Autobiography, There is Someone with me. And He has asked me to get up because there is work to be done.” And so, chief amongst the propaganda works, Kurelek set out to illustrate all of St Matthew’s Gospel, beginning with 160 scenes of the Passion. To this end, he travelled to the Holy Land in 1959, and returning to Canada soon afterwards, he embarked upon the St Matthew’s series on New Year’s Day 1960 with the goal of painting one per week over the course of three years. The series was ultimately exhibited at the St Vladimir Institute in 1970, and purchased in its entirety by a Ukrainian couple, the Kolankiwskys, who hung them in their new gallery in Niagara Falls.

by Gertrude Perpetua

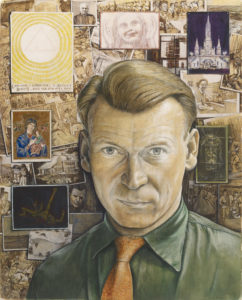

Self-portrait 1957