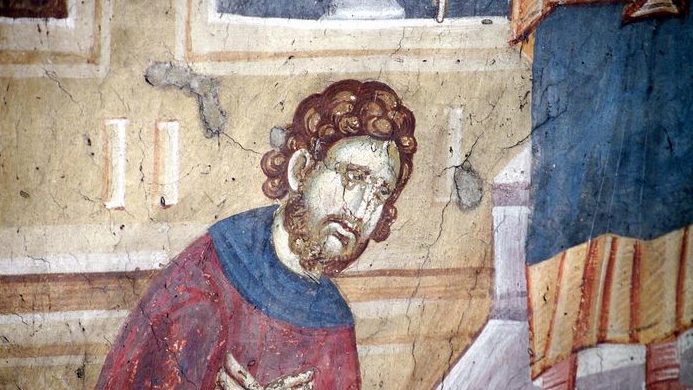

04 Sep Reflections on the Publican and Pharisee

The Publican and the Pharisee are proverbial in Christian consciousness. And so we imagine that we know immediately and instinctively the contrast that is being shown us: hypocrisy, on the one hand, and humility, on the other.

But perhaps things aren’t quite so simple.

Let’s take the Pharisee first of all. Is he really a hypocrite? Against this, there seems to be no suggestion that he is lying to anyone, not even to himself. I fast twice a week, I give tithes of all that I possess. At no point does the parable invite us to conclude that these claims are untrue. On the contrary, the Pharisee is presented as a religiously observant Jew, faithful to what the Law demands.

Nor is his fidelity merely a matter of ritual, an arid exteriority. He is also morally observant, interiorly self-disciplined: I am not as the rest of men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers. And again, there is no suggestion that the Pharisee is being merely dishonest.

Likewise, when we turn to the Publican, there exists no implication that when he acknowledges himself a sinner he is engaging in that exaggerated but apparently virtuous self-abasement which some people take for the virtue of humility. Perhaps, on the contrary, he too is simply speaking the truth.

So our instinctive interpretation doesn’t really fit the facts. The Publican isn’t a good man humbly claiming to be bad, any more than the Pharisee is a bad man hypocritically claiming to be good. Instead, each is representing himself truthfully. But having got this far, we now face another problem. For we are told that it is to the Publican, the sinner, rather than to the Pharisee, in his virtue, that God draws near. And we may reasonably ask how can this be.

In trying to answer that, it is tempting to wonder if virtue may not, after all, be somehow small, inward-looking and self-regarding, whereas sin is perhaps large, uninhibited, and adventurously free of self-regard. On this view, the mercy of God is not attracted by those striving to convert from sin and become holy. On the contrary, God’s mercy is drawn to those who embrace their sinful condition, who sin and who know that they sin, and are accordingly free of self-aggrandizing fantasies of repentance, sanctification and reward. We might start to wonder whether it is the sinner, and he alone, who truly knows himself and who therefore can authentically reach out for forgiveness. The virtuous, by contrast, we may begin to view as a lesser soul, incapable of extending himself towards God because confined by a childish spiritual narcissism. He has no interest in being forgiven, but desires only ways of seeing himself as meritorious and vindicated in God’s sight.

Now there is something right about this line of thought, but also something very mistaken. To help us to discern true from false in this area, we should recall the very striking fact that St Philip prayed that his virtues be hidden, not only from others, but even from himself. His prayer was not against being virtuous, of course, but against knowing himself as such. We might say that he desired to live as the Pharisee lived, but with the self-understanding not of the Pharisee but of the Publican. But why pray for that?

I think St Philip prayed like this because he knew that if his virtues were not hidden, and especially from himself, then he would inevitably come to think of them as his, as excellences which, even if they had initially come from God, were now securely his own. And, like all the saints, he knew that this would embody a profound mistake. For saints do not possess holiness, but rather they share, or participate, in the holiness of Christ. Any of us, in so far as she has anything pleasing to God, shares or participates in what is His and His alone. It is ours only to the extent that Christ draws us into Himself and sustains us in what this makes accessible to us. Virtues, sanctification and holiness are, in other words, never private property. They are not even property which will one day become private, in eventually being permanently made over to us. For the deeds of this property are always Christ’s, in this life and in the next; we are only ever His tenants.

Which means that our dependence is as radical as can be, encompassing us beyond all comprehension. But nonetheless we try to grasp it, and in doing so we inevitably distort it, transposing every virtue in which Divine mercy permits us to share, into an excellence which self-love reformulates as its own. This is precisely the transposition accomplished by the Pharisee. And so St Philip prayed not to know the virtues He owed to participation in Christ. He desired, like the Publican, not to be wrapped up in his own excellence, but to know himself only according to what was truly his, and his alone: in other words, to know himself simply as a sinner and nothing else.

O God, be merciful to me a sinner. To desire everything that Christ wills to give, but to know oneself only as always being in need of it, and therefore to live out the mystery of redemption in radical poverty of spirit – this is the heart of sanctity, in which we are increasingly, and painfully, purified from a self-regarding spirit of possessiveness which is otherwise unconquerable. A self-conscious and acquisitive virtue, intent chiefly upon contemplating its own perfection – the disposition of the Pharisee, in other words – is profoundly self-defeating, precisely because profoundly self-centring. The Publican, by contrast, is a refugee from self-possession, seeking himself not in himself but in God, willing to be entirely indigent except according to the provision which Divine mercy alone can make available to him.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.