02 Oct Reflections on Forgiving

‘Seventy times seven’, in the Gospel, isn’t, of course, a specific number. What it means is that we are called upon to forgive without limit, as many times as forgiveness is asked of us, however frequently that may be. And it implies, as well, that our forgiveness is meant to be unlimited in another sense: there is to be no restriction on the kinds of injury we are prepared to forgive. We are to be always forgiving not just in some things, but always in everything.

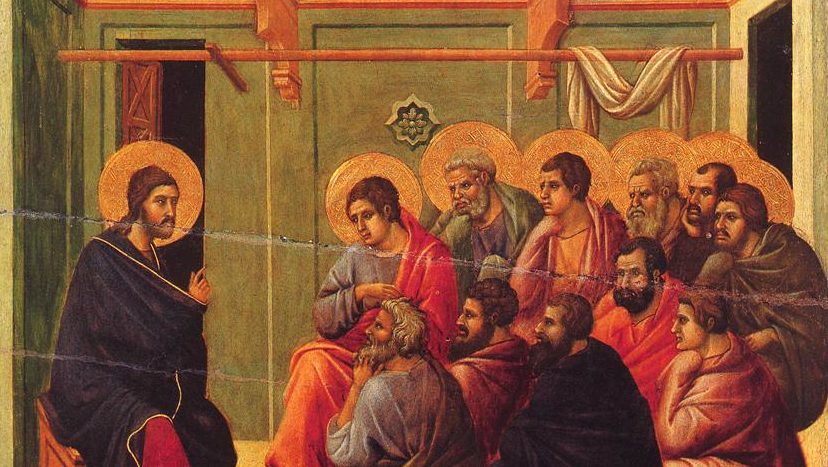

Doubtless this appears too much to ask. But the Gospel not only asks this of us, but also shows us how we are to interpret what is asked of us. And at the heart of that interpretation lies the idea of cancelling debts. In the parable of the Master and the two servants, debts exist only so that they may be extinguished; they are recalled only so that they may be withdrawn. Only the first servant, who understands nothing, insists that debts must be paid.

It is in the withdrawal and extinction of indebtedness that forgiveness consists. What gets forgiven is what is owed. This means that the person who forgives doesn’t ask for anything to balance the injury he has received, he forgives precisely by foregoing every claim to compensation or restitution. Forgiveness overwrites obligation: forgiveness sets free. And not only does it free the one who is forgiven, but also the one who forgives. In forgiving he frees himself because, having forgiven, he is no longer obliged to seek satisfaction from the one who has injured him, just as the one who has injured him is no longer obliged to offer it. And so, beyond the accounting demanded by justice, forgiveness re-creates everyone who shares in it. Justice, we might say, merely corrects the world, whereas forgiveness makes it new.

Now we might still think that, even on this interpretation of what forgiveness requires, its demands are too great. But at least we can now see that the call to forgive doesn’t depend upon bringing about a particular kind of feeling – for example, no longer caring about having been injured, or liking the person who has harmed us; and nor does it require that we somehow forget our injuries, consigning them to an unremembered past. Sometimes we find that such states of mind can accompany the practice of forgiveness, but they are not at all what forgiveness means, and in any case are impossible to produce; whereas forgiveness is always possible, once we have understood what is involved in practising it, regardless of what we remember and how we feel. Forgiveness requires only one thing: that our bottom line, concerning those who have injured us, ceases to be an insistence on an indebtedness which justice requires them to discharge. Once we surrender that, then forgiveness is accomplished.

And now we can go further. It is not forgiveness that is impossible, in fact, but the alternative to it. What really does prove impossible is adherence to justice, indebtedness and restitution. There are at least two kinds of reason for this.

The first is that restitution is always a kind of fiction, restoring at best a merely symbolic equilibrium. Nothing can erase injury, because injuries are always already undergone and nothing can undo the past; besides which, no injury can be adequately measured or grasped, which means that producing a compensation truly corresponding to it is hopeless from the start.

The second problem is this. None of us is merely injured, but every one of us is also an injurer: harm is not only something we suffer, it is also something we do. And because of this, how can we construct even a merely symbolic system of restitution with any plausibility? For perhaps the injury you have done to me compensates the injury I myself have done to someone else, but does so only imperfectly, which means that I in fact have no right to claim any compensation from you, since my own overall indebtedness is in fact greater than yours; what I need from you, in fact, is not compensation, but even more injury, to make up for the harm I have done elsewhere. In that case, however, what about your obligation to compensate me, as opposed to my entitlement to claim it; and what about the indebtedness of those whom I myself have injured, for they themselves have of course done harm as well as suffered it? As we can see, very quickly the attempt to work out the arithmetic of justice leads to a kind of insanity, involving infinitely elaborate estimations of kinds and degrees of reciprocal indebtedness which are, in fact, incalculable.

We might imagine, in fact, that the whole question is so complex that it must be left to God to work it all out. But I think that what the New Testament shows us is that God has very little interest in doing so.

For Christ doesn’t redeem us by compensating for sin and its effects, for the harm we do or the harm we suffer. Rather, He carries the weight of it Himself, showing us how to bear it, acknowledging it without being confined by it. Bearing the burden of another, so as to convey to him the strength to bear it himself, takes us beyond anything justice can conceive. In Christ, our indebtedness is not paid, but surpassed; obligation isn’t insisted upon, but transcended. And so what He achieves isn’t the perfect resolution of competing claims, by a kind of supernatural arbitration. Instead, Christ inaugurates a community founded differently. This community, which is the Church, always commences in the practice of forgiveness: in receiving it and in offering it, so that indebtedness is no longer the determining horizon of our lives. And from this forgiveness the Church unfolds and flourishes solely according to charity. As Christians we do not seek to fulfill obligation, but to live in imitation of the love that is offered us.

For neither towards God nor towards each other can we ever render ourselves un-indebted. What we owe to God and to each other always exceeds what we could ever repay. So if we insist on justice, indebtedness and restitution, we will necessarily end up, like the first servant in today’s parable, imprisoned by undischargable obligations. He cannot pay what he owes, but because he insists on receiving compensation, neither can he find release; even though forgiveness is offered him, he cannot receive it, because he cannot think beyond the horizon of indebtedness, but only of escaping his own, while insisting on that of others. For him, as for all of us, receiving forgiveness and showing it are indivisible.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.