29 Nov Reflections on the Mystery of Christ the King

And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me’. Reflecting on these words will bring us to the heart of the mystery of Christ the King, because it will bring us to the heart of the mystery in which His Kingdom consists.

What we have to understand here is that when Christ identifies Himself with the least of His brethren, this isn’t a mere figure of speech that He is using. Nor is He telling us about a mere way of looking at things, meaning that whatever is done to the brethren will be regarded as if it were done to Himself. Instead, He means us to take what He says literally. The brethren and Christ are one, so that whatever is done to them is also done to Him. This is the mystery of which He speaks, and the difficulty we face is arriving at some understanding of how it can possibly be true.

The truth of it, however, lies nowhere else than in the Incarnation itself. In becoming flesh, the Word of God took human nature to Himself. And the consequence of this is that, in Him, human being becomes the medium, the language if you like, in which the eternal life of the Son of God discloses and expresses itself. Because of the Incarnation, then, human nature and human existence are empowered not only to speak about God, but actually to speak God Himself. And this is because, in Christ, God no longer merely speaks to humanity, but now He speaks in and through humanity itself.

Moreover, in this extraordinary communication between Divine and human, the Incarnation brings humanity to the completion which God has always intended in creating it. This is the reason why the Incarnation does not require a new human nature to be fashioned in order for the Son of God to unite Himself to it. On the contrary, human nature from the beginning had this capacity to be united to God, and it was for the sake of this union that humanity was brought into being. The Incarnation, then, is the event of humanity’s fulfilment.

And this fulfilment, of necessity, touches everyone. It touches everyone because the Incarnation reveals the meaning, not just of some human lives, but of every human life, without exception, whether we know it or not. For St John tells us, at the very beginning of his Gospel, that in the Incarnation the Son came unto His own. Let us consider these words: He came unto His own. What this means is that when the Son is revealed in our flesh, every one of us is shown the One to Whom he already belongs, simply in virtue of being human. Every human being is already in His image, fashioned through Him and for Him. Human beings as such are brethren of the Word made flesh. To be human, then, is to mean, not just ourselves, but the Incarnate Son. Humanity speaks, not only of itself, but of Him. And this is because, from the beginning, He speaks us in order to speak Himself.

Here, then, we have the foundation of the Kingdom of the Incarnate Word. That Kingdom is rooted in the belonging of all humanity to the Word made flesh. Everything else in Christianity flows from this primordial belonging. And this, at the most fundamental level, is also why our conduct towards each other is at the same time conduct towards Christ Himself.

But we still have to ask why the emphasis falls particularly on the least of the brethren. The brethren, after all, encompass everyone. What is so special about the least of them? The answer, I think, is that it is in encountering the least of the brethren that our resistance to the Kingdom is most keenly felt, which means that it is in this encounter that our understanding of the Kingdom is especially tested and deepened. For the least of the brethren are of course the poor, in one or more of the many forms that poverty in human beings can show itself: material, physical, moral, intellectual, spiritual. And in any of these forms, once we discern it, poverty proves repugnant to us, and so we tend to flee from it, refusing community with it, and preferring instead to belong only with those who delight or flatter us, or in some other way insulate us from acknowledging our own vulnerabilities. In other words, we find that poverty obscures humanity, it gets in the way of allowing us to see that humanity is intrinsically vulnerable, and therefore, in a certain way, visible most of all in the vulnerable. And so we shy away from this visibility of humanity in the poor, thereby failing to allow ourselves to see humanity as it truly is. And this means, as we have seen, that we fail also to see Christ as He truly is, and therefore also His Kingdom, and finally God Himself, Whom Christ and His Kingdom reveal to us.

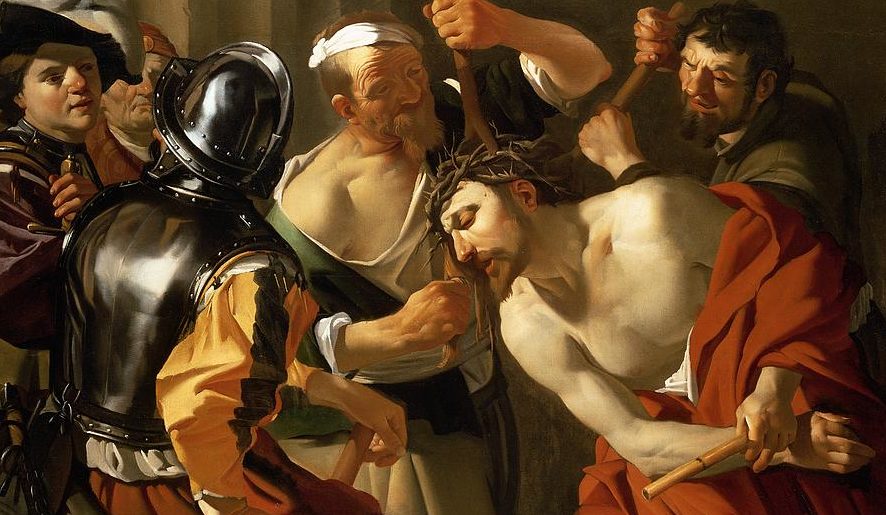

In the poverty of Christ, at the foot of the Cross, we encounter the heart of our resistance to the Kingdom which Christ reveals. And it is for this reason that we are called to abide with the Cross, even to embrace it, as in some sense the permanent sign and meaning of the Kingdom. Our community with the least of the brethren is one expression of this. For in them, and of course in our own poverty, we dwell with that vulnerability in humanity through which the Son of God chose to speak Himself, on the Cross, with the greatest eloquence.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.