06 Feb Reflections on Poverty and Faith

St James tells us that God chooses those who, though poor in the eyes of the world, are nonetheless rich in Faith. In this teaching, poverty and Faith are not just two states of being which God happens to have brought together. Instead, they are deeply, inwardly connected. To see how, think of our practice of reciting the Creed. We say that we believe certain propositions, propositions which are expressions of Faith in words and ideas. But Faith does not rest in words or ideas; it rests in the life of which the words and ideas speak. And the life of which they speak can be understood only as the life of God Himself: the Trinitarian life of love in which, through Faith, we are called to share. This sharing through Faith is indeed a kind of wealth: it enriches those who are drawn into it. But its abundance is a Divine abundance, the abundance of love, which in Christ is revealed to us as founded in giving rather than in receiving – or rather in receiving for the sake of giving. And what this means is that the riches of Faith are not a matter of possessing what we have, but instead of giving it away, of being dispossessed. We share in this dispossession in union with Christ, by sharing in His love for the world inspired in us by His Paschal Mystery.

Poverty, then, lies at the heart of a living Faith. We miss the point if we think that this essentially means material poverty. It may be that material wealth makes the poverty of Faith more difficult to live. This is because material wealth tends to infuse our lives with confidence in what we possess, making repugnant, and perhaps extinguishing altogether, the readiness for dispossession which Faith demands. But it would be wrong to suppose that material wealth makes this inevitable, just as it would be sentimental to assume that material poverty ensures the opposite.

Christ Himself speaks of the poverty of Faith as poverty of spirit. This is a wider and deeper category than either wealth or poverty in the material sense can comprehend. Poverty of spirit is a radical openness to the God of love; it is opposed by anything that makes the dispossession involved in a living Faith seem unattractive or even unendurable. In many different ways we tend to insist on personal enrichment, on having something – anything – which here and now can be possessed and delighted in as our own. And this refusal isn’t necessarily rooted in what we might think of as worldly, material pleasures. Religion itself can provide opportunities for it. We can get so caught up in identifying ourselves as people of Faith, so possessive of its history and customs and politics, that we lose sight of the sharing in Divine life in which Faith most fundamentally consists. We can find ourselves, in the name of Faith itself, resisting the dispossession which Faith demands, choosing instead the visible, palpable consolations of religion. We forget that Faith gives us access to the Divine life of charity, reducing Faith instead to the level of a merely human activity.

Of course Faith is a kind of human activity; but if this activity is to be true to itself, it will tend towards poverty of spirit, rather than self-enrichment, as its most fundamental guiding orientation. Poverty of spirit, which is the true imitation of Christ, draws us away from cultivating religious practice as a substitute for the life of charity. And, in union with Christ, poverty of spirit teaches us that we cannot expect the life of charity to be something in which we necessarily take pleasure or find consolation. As many of the saints in their different ways show us, Faith can be lived even though nothing is felt, sometimes not even Faith itself. Such experiences are not contrary to Faith, nor are they special experiences reserved only for the few. On the contrary they illuminate what Faith really is: the confidence we place in Christ crucified.

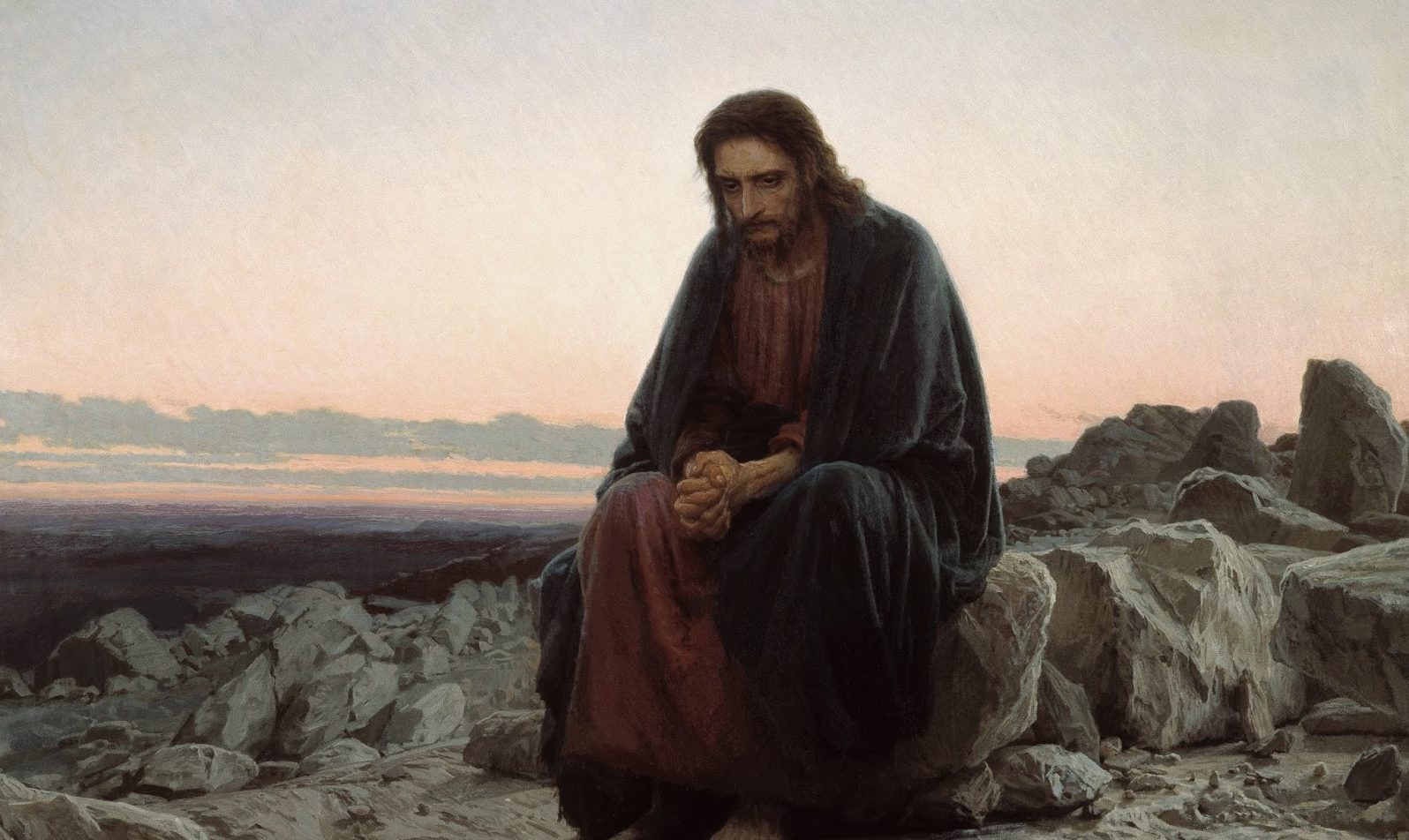

We can see such poverty of spirit manifested in the Gospel. We are told that just before healing the man who has been brought to Him, Christ [looked] up to Heaven [and] sighed deeply. These movements are a distillation of Faith. It is as if Christ does not possess in Himself the power to heal this man; instead He asks for it from above, and waits for it to enter into Him, looking to the Father in poverty and trust. He knows that He can have nothing except what the Father will give Him. But He does not ask for something to be given which He can then possess for Himself. Instead He asks for a gift that will be given Him only to pass through Him, into the man who needs healing. He asks to receive, but only so that what is received may in turn be given away. In all this Christ shows us what the life of Faith looks like, by adopting its most fundamental dispositions as His own.