22 Aug Reflections on Vulnerability and the Logic of Scarcity

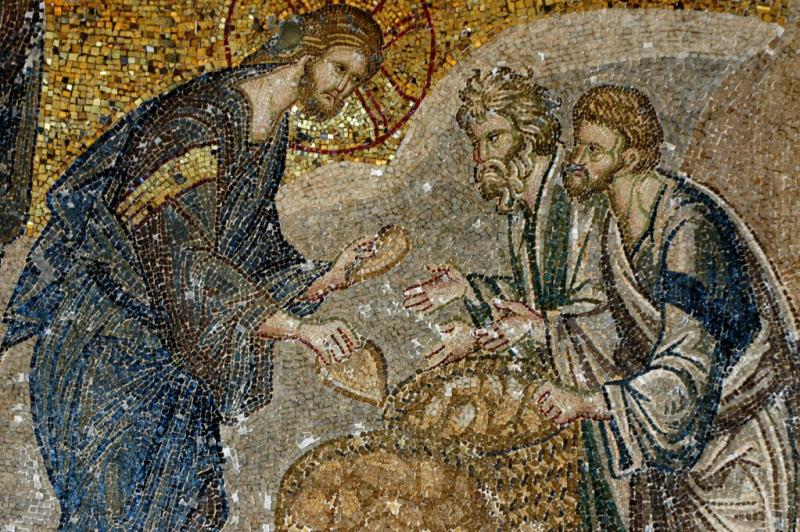

Although the miracle of the loaves and the fishes isn’t in itself a miracle of the Eucharist, it is nonetheless a miracle we can describe as Eucharistic. This isn’t just because it points to the Eucharist. The miracle is Eucharistic in a deeper sense, because in itself it reminds us of dimensions of the Eucharist we can easily overlook. So we must not only think of the loaves and the fishes in light of the Eucharist; we must also think of the Eucharist in light of the loaves and the fishes, finding there Eucharistic meanings we might otherwise neglect.

The meanings in question centre upon the human experience of vulnerability and scarcity.

First, vulnerability. The Gospel opens with Jesus, hemmed in by the crowds, curing those who are in need of healing. Immediately we are made aware of our fragility. And fragility makes us uncomfortable. We desire to be in charge of ourselves, independent and autonomous, and yet our humanity tells a different story. We are more vulnerable, and our lives are more interdependent, than we like to think.

Second, scarcity. The crowds in today’s Gospel are hungry, but there is apparently too little food to go round. With resources running so low, the Apostles draw what seems the obvious conclusion:

Send the crowd away [they tell Jesus] to go into the villages and country round about, to lodge and get provisions…we have no more than five loaves and two fish – unless we are to go and buy food for all these people

In these words, human unwillingness to face its own vulnerability is accorded an all too familiar rationalization, which goes something like this. Scarcity of resources means that there are some people who cannot be helped, even though they are vulnerable and in need; such people must therefore be sent away. It is simply unavoidable that some people have what they need to survive while others do not. And since this is unavoidable, it must presumably express God’s will towards us.

But as we can see, today’s Gospel makes clear that God’s will is in fact quite otherwise. Jesus refuses to accept the Apostles’ determination to be rid of the human vulnerability that surrounds them; and likewise He refuses to accept their unquestioning reliance upon the logic of scarcity. Instead He first of all commands that the crowds remain. And then, from the scarcity that had seemed so definitive, He produces an unforeseeable abundance:

And all ate and were satisfied [the Gospel tells us]. And they took up what was left over, twelve baskets of broken pieces.

It is here that we can begin to see the importance of this miracle for our understanding of the Eucharist. When we consider the Eucharist in light of the miracle, perspectives that we might otherwise neglect are opened out for us.

First, then, we can see that the Eucharist does not fear human vulnerability, but embraces it. This is already hinted at in the twelve baskets of broken pieces left over after everyone has had his fill. The very substance by which the people are restored reflects their brokenness in its own: it savingly shares in the frailty of those whom it rescues. And this reminds us of the solidarity with our brokenness that the Son of God Himself accepts, in the vulnerability of His body that is handed over for us and His blood that is shed for us: in short, in the whole of His mortal frailty which the Eucharist proclaims, and in which it allows us to participate as our passage to eternal life. In the Eucharistic body and blood of Christ all human vulnerability can shelter and find its remedy, because the Son of God Himself fearlessly took shelter in that same vulnerability, disdaining no one He found there.

Which means, secondly, that in the Eucharist there is no logic of scarcity: no interplay of acquisition and enrichment for some, deprivation and impoverishment for others. God’s resources show themselves to be unlimited, apparently even wasteful: when everyone has eaten as much as he desires, there are still twelve baskets left over, a sign that Divine giving is entirely uncalculating and inexhaustible. And it is of course pre-eminently so in the Eucharist, where the only limit to God’s generosity is to be found in ourselves who receive it.

It is in Christ, and especially in His Eucharistic self-offering, that we have learned how vulnerability can be accompanied and made sanctifying, and how, in God’s eyes, there is no such thing as scarcity of resources. Creation, in the beginning, understood this; but now, because of sin, we have obscured from ourselves the Divine generosity by which our world is sustained, which is why we have to learn it as if it were for the first time. The Eucharist is given to us so that, mysteriously but effectively, we can begin to retrieve the truth of Divine generosity and, by sharing in that generosity, bring creation to its consummation.

By Fr Philip Cleevely, Cong. Orat.